HUMOR MAXXING: METHODISTS & METHO-DAOISTS (Part 3)

The Ingredients of the Golden Elixir

Part three of this essay is an introduction to the idea that the meditation practice called the Golden Elixir has many diverse ingredients.

I use a rambling style because the Golden Elixir itself is unwieldy, its content imposes sudden juxtaposition, reversals, incomplete lists and other such things. Long before the Golden Elixir was a lineage phenomena, before Daoists even settled on a name for it, it was an experimental tradition of enormous diversity. Ages later it became common for Golden Elixir texts to begin with a warning that if you transmit or practice this text inappropriately your life will be shortened; you will die; you will end up in a special hell reserved for the literate elite in an endless cycle of being breaded, deep-fried, re-vivified, and then deep-fried again. This is because for me to transmit the Golden Elixir to you, our personalities, appetites, qi levels, charisma, strength, intelligence, timing & other such things must align; our xingming must be a match. [Xingming is a bit like one of those Dungeons & Dragons Character Sheets popular in my youth. If I am forced to translate it, I’ll go with appetites & circumstances.]

Continuing our discussion of the view, method and fruition of the Golden Elixir, it is worth re-stating that I would leave off the method part of the discussion entirely, because by itself it isn’t Daoists, but it is the knot that needs untangling at this moment in internet history. As long as we keep in mind that view and fruition are the main subject, a detour into the ingredients of our methods will be fun.

To illustrate this point, consider music. A few years ago I had an email exchange with Daoist Music expert, Stephen Jones. I began by gushing about how extraordinary and inspiring the musicians he brought to the Daoist Conference in Paris were, and praising the music he recorded in situ. He responded rather coyly that the music itself wasn’t Daoist because centuries of Daoist ritual creators have assembled their music from local varieties. On the surface, this would seem to conform to my notion that methods themselves (musics in this case) are not Daoist. But to the contrary, I objected. The Daoist music in question, to my ears, was a profound representation of Daoist cosmology. Vibrating reeds and drums fill the space, their timbres stretching across a huge swath of the audible spectrum. An individual suona, double-reed horn, cut through and sounded a melody, I could follow it only to have it dissolve into a chaos of other horns bouncing off all the walls and corners in unpredictable ways. Just as suddenly another melody would emerge, already formed, without any beginning, and then again, disappear into chaos. Standing in the room while these Daoists played, I found myself polarizing between a frenetic impulse to move, and a deep recourse to inner stillness. [Check out Stephen’s blog, tons of great Daoist music there]

The second easiest way to describe the Golden Elixir is: transforming nascent sexual energy into creative potential. This is so obvious & true it is hard to explain, it is also too general because consciously or unconsciously it is the reason a lot of people do yoga or go to the gym.

The easiest way to describe the Golden Elixir is: disassembling the constituents of our being and then reassembling them. Even when we engage with easy and simple methods, one can see that view and fruition are implied. What views would suggest transforming nascent sexual energy, or reorganizing the constituents of our being? What type of fruition might we gain from it? It’s a pretty open road isn’t it? That’s why it isn’t Daoist unless the view and fruition are Daoist. Section 4 of this essay will focus on fruition.

The foundations of Daoist religion are in the felt experience of wuwei (not doing). Wuwei is not by itself a style of meditation, rather it is a conceptual framework for understanding view and fruition. Wuwei is the first of about twenty conceptual frameworks contained in the Daodejing which give order to patterns of human conduct. Patterns & conduct, or rituals and precepts, are inventions that we use to navigate change. If you think about it, there are three ways to respond to change, the tragic approach, you can resist it; you can try to match it, cool idea but you’d have to be an oracle to pull it off; and the comic approach, you can over-change. Most religions favor the tragic approach. Daoists favor the comic approach and practice over-changing. Daoism is unusual because it does not assume to be in a conversation with people on the brink of survival.

Daoism is the religion of letting things change you. Daoism’s original audience was the indolent prince who has all his needs met and more power than he wants. Wuwei is a body commitment. Wuwei is a body-oriented approach to change; an openness to the possibility of not constantly falling into trance, not attempting to perfect ontology, and not accepting the idea of sacrifice.

Diversity of Golden Elixir explanations, a History

Explicit descriptions of meditation in pre-China start around 450BCE. [See “Neiye” section of the Guanzi.] The Daodejing and the Zhuangzi (~300 BC) both describe meditation abstractly, leading many disembodied scholars to caution against interpreting these texts as clear examples of meditation instruction. But this is wrong. The first explicit Golden Elixir texts, The Yellow Court Scripture, and the Cantong qi, quote directly from the Daodejing, adding context that makes it clear that the authors of these later texts viewed the Daodejing and the Zhuangzi as sources of the Golden Elixir. Perhaps the “problem” is that the Daodejing is just too perfect in its focus on view and fruition, avoiding explicit descriptions of method.

Take a look at Daodejing Chapter six for example:

The Valley Spirit is Deathless,

It is called the Dark Mare,

The Door of the Dark Mare is the root of Heaven and Earth,

Delicate fluff of a fluff, it barely exists,

Yet drawn upon, it is inexhaustible.

The earliest commentary on this Chapter is He Shanggong, who explains this chapter as the use of sexual energy, breath and nutrition to remake the body from its original constituents. Although He Shanggong does not use the specific term Golden Elixir, the concept is flushed out.

Modern readers sometimes make the error of trying to insert a metaphysics here; meaning this fluff of a fluff is some kind of disembodied god-spirit-creator-agent. But there is no metaphysics in Daoism, everything has a body. Fruition is available in the “tiniest fluff of existence.” The closest Laozi gets to a method here is to describe a womb, the dark mare (lit: dark female animal), which is darkness inside of darkness, inside of darkness, where all things are cultivated.1 The view here is that there is something about us which is deathless, or not-dying, and inexhaustible. It specifically doesn’t use positivist language like “lives forever,” it just doesn’t die. These old commentaries do not go metaphysical with this, they stick with the body. They say there is a part of our body, an undeclared ingredient if you will, which persists beyond our death.

Practicing the Golden Elixir with a change-resistant tragic view is the epitome of frustration. Yet people seem to be teaching that. They say it is something “you” do, often to “fix” something that you “are.” That’s tragic because you would still be you when you finished it. The authentic starting place is that it is something you don’t do. This is expressed by a key term from the Daodejing, ziran, self-arising, or so-of-itself, spontaneous.

Next we have early Han Dynasty tombs with princes completely wrapped in suits made out of small jade tiles. The idea, we think, was to keep their bodies from decaying which itself was to have some role in preserving their integrity in an afterlife. The Chinese see Jade as a liquid moving so slowly it appears as stone. Jade thus represents epic periods of time and power. The argument that there was some concept of an afterlife at this time is strong. We just don’t know much about how they conceptualized it. Tombs from this era also contain recipes for extending or preserving life; listing plants, fungus, minerals, daoyin [quick into to daoyin this video], and spells. The stuff in these tombs poses the question, what did they think death was all about? These princes were also buried with libraries! Why? Was death a good place to catch up on reading? And enjoy prized possessions. There are jade lamps with images of immortals with wings flying around in misty mountains. There are carved jade dishes designed for capturing the morning dew on sacred days, the dew was mixed with medicines and ingested, an early model for the Golden Elixir. This idea of the immortal (xian) is the subject of the next essay, number 4. It changes over time paralleling the many unique techniques for making the Golden Elixir.

One is inclined to think that practitioners of the Golden Elixir saw death as an opportunity for performance art. This is certainly the case in many cultures, no? In Ghana I danced at a funeral, where the deceased was entombed in a casket painted and shaped like a mackerel, placed in front of a tableau of fabric waves and a fountain. After learning that Taiwanese gentleman, affiliated with the underworld, hire strippers for their funerals, I asked my father if he would like me to organize an orgy for his journey to the other side. The tragic view of death really puts a damper on the fun we could be having at funerals.

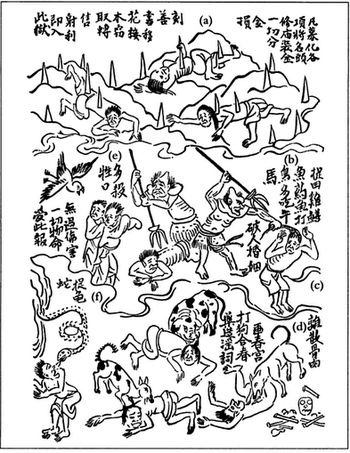

Another type of Golden Elixir involves visualizations of hell inside your body. It used to be that you'd go to hell for like a billion years, and hell was the worst bureaucracy imaginable, not just waiting in lines but being tortured by customer service. Then they decided a billion years was too long, so they switched it to three. After three years you have to drink a soup that makes you forget and you get reborn. We Daoists are the most believing people in the world, we over-believe, we super-believe. There are many other death options too. Death, as performance art, can be sad or fun, cute, dark, strange or sexy. I will leave this hanging here, you can read about Daoist hell elixirs here if you want to [Picturing the True Form], but know this, Daoists control the existence and nature of hell, we are not to be trifled with.

Golden Elixir ingredients are diverse. The point of all these recipes is to give you the idea, not to make you an expert in methods.

A powerful way for us moderns to understand Golden Elixir recipes is to look at each ingredient as a nameable experience which self-arises from cultivating stillness. Cheetah House has compiled 59 possibly negative “symptoms” of stillness. Most of these are also Golden Elixir ingredients. The list came about because methodists pitch meditation as a cure-all. Daoist meditation has no purpose, so it is inconceivable that one would persist in, for example, cultivating self-arising phenomena like “no concept” to the point where one would no longer recognize what a red signal light means; That’s obviously quite dangerous, by the way, and Cheetah House has documented this happening. It is the kind of thing that can happen to people who believe meditation will cure them of anxiety, or people who leverage meditation as a cure for self-hatred. The Cheetah House list is not a complete list of Golden Elixir ingredients, the actual number is 108 because besides being “effects” of stillness they are also potential hell realms and there are 108 of those.

The 108 “ingredients” of the Golden Elixir are standard but also secret. Each Golden Elixir is a unique mix of self-arising ingredients. How could this be? Why? Why is Daoism so different from Buddhism, by the way? given that most of the “ingredients” on this list were taken from Buddhists.

Recently, I was reading an internet Golden Elixir teacher and he said that the reason descriptions of the Golden Elixir use coded language and obscure analogies is because they wanted it to be secret. But then he didn’t explain why it should be secret. He is wrong. The coded language at issue here is artistic expression of something rather ineffable, which never the less exists. The analogies used to describe the Golden Elixir were not obscure in their original historic contexts. They are like talking about sex using baseball terminology. “The other day I was just rounding third base when my raven-haired neighbor rang the doorbell.” If you read this 500 years from now when doorbells and baseball no longer exist, that third base metaphor is going to be pretty confusing. Anyway, that internet teacher never explained why the Golden Elixir is secret, but I will tell you: If you practice without the proper initiation you are likely to treat it as a method and become frustrated. Daoists don’t want you to be frustrated. There are even some dangers, this frustration can lead to nihilism or sado-masochist rituals. In short, the Cheetah House list of meditation errors is also an awesome list of ingredients.

The secretness of the Golden Elixir was never very secret. Zhu Xi, the central organizer of Confucianism in the 12th Century, was familiar enough with the Golden Elixir to offer a commentary in which he rejected it because it does nothing to further the interests of the state. Literally every educated Chinese person for the last thousand years was familiar with Golden Elixir to some degree; at least enough to be thoughtful, self-reflective, or dismissive about it.

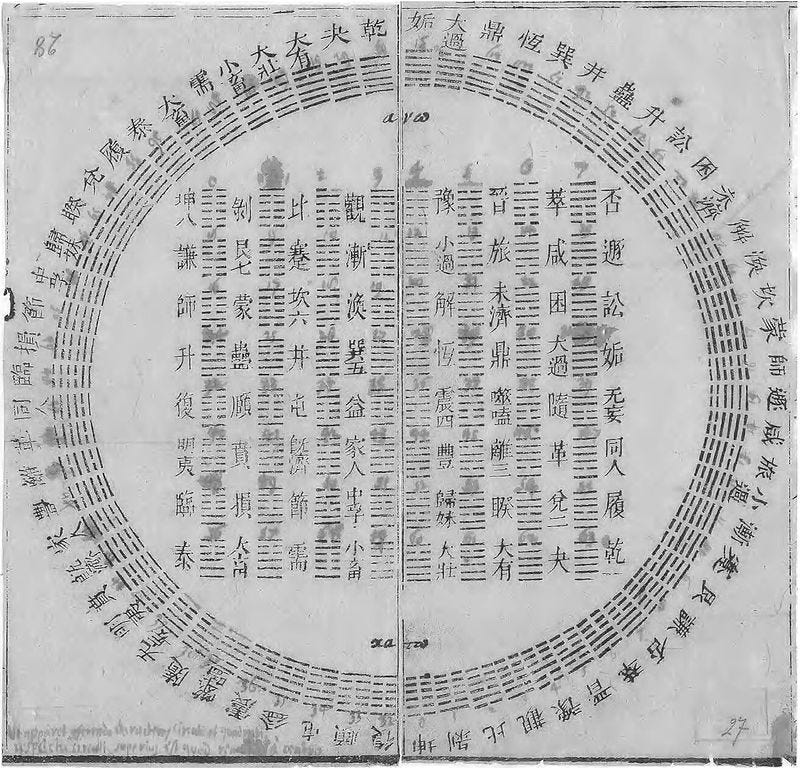

The use of the Yijing to describe and organize Golden Elixir teachings was common because memorizing the Yijing was so common, it was like baseball. [Robenet explains in depth for those who are curious.] The Yijing is also part of Daoist ritual where it serves to categorize deities spatially. I know, too much information, but the Yijing is a divination system. That’s right, it’s for guessing. Or rather, like Tarot, it is a tool for psychically externalizing your guesses. It does not exist to make the Golden Elixir harder to learn.

Practicing the Golden Elixir was a prerequisite to learning medicine in the Ming Dynasty, we have copies of the curricula they used. [Elisabeth Hsu, The Transmission of Chinese Medicine.] It’s called a secret because it is your personal unique secret that you haven’t discovered yet!

Also, it is possible to discover new ingredients! Yes! The recipe you use has to be your own, and it has to be unique, spontaneous, and self-arising. But the existence of standard ingredients means you can potentially follow someone else’s recipe for a time. It is a way to jump start your own recipe. Chinese comic literature is full of people who got their elixir from someone else. The most common version of this story is that a discarded sperm grows into a demon (jing 精) and wreaks terror on a village, before being transformed into a warrior-servant of an elemental god (shen 神) by being forced to ingest some of the god’s elixir sperm (jing 精). We also have examples of a person’s elixir being used to heal someone else, or gifted to someone else in the form of an ability usually as a reward for merit. Or they get it by having sex with a fox spirit (this happened to me). But these are “incomplete” elixirs, in that they don’t develop. These are methodist elixirs not Daoist Elixirs (Fashi vs Daoshi essay 1).

Sometimes an immortal comes down from a mountain or from the sky to help a budding Daoist jumpstart their elixir. This is a common story. It is a modest way of saying you figured it out yourself, without a lineage. This is what it means to credit Zhang Sanfeng with the creation of Tai Chi, but people are so confused they think it refers to a historic person. Daoism is so old that lineages less than a thousand years old are not taken very seriously. But, as Laozi says, “Daoist adepts are always helpful and leave no one out!”

Perhaps you have heard the reductionist description of the Golden Elixir, which is a circulation of qi that goes up the back, down the front, repeat a bunch of times, then qi rises up the center, collects like dew in the head, descends to the mouth where it is swallowed down to the heart which then opens like a flower and expands in all directions before returning and sinking to start the circulation all over again. Sad. The analogies and poetic images in this description have all been downgraded to body parts. The head where dew collects is more like an infinite sky dome. The qi that goes up to the head is magical pre-sperm so potent it can open up portals to palaces full of etherial beings waiting to assist you. The reductionist description is even missing the differentiation of jing, qi, and shen as it arises spontaneously from stillness. Just because something has no use doesn’t mean it has to be boring.

The realms of history, religion, and fiction were blended in traditional China. If we ask, “What did people in China think the Golden Elixir was all about? What are the continuities across time and culture?” It turns out that theatrical literature is the best source for how people thought. There is no Golden Elixir without art. Among the many reasons why I reject the methodists is that they are reductionist art-neglecters. Historically speaking, wilder is better.

The Oldest version of the Golden Elixir that academics agree on are visualizations of deities installed in infinite cavities of kinesthetic emptiness. I wrote about this in my book. These gods are located in specific parts of the body, thus they appropriate things we would call hormone effects, sentiments, organ functions and such. But the preliminary is the establishment of infinite emptiness in these locations or caverns.

Such elixirs are highly individual, if for no other reason than there is a continuum between people like me who find imagining anything in exquisite animated detail with all five senses extremely easy, while others struggle to simply visualize a sumptuous apple pie.

In reality, my perception, my eyes, my hormones, my pheromones, my organs, construct meaning through pockets of reducibility [See essay 2]. I have a sense of what is behind me, I’m not actively visualizing it. It’s just there. It is a passive process. The fact that my peripheral vision is in focus and not blurry is do to my mind creating pockets of reducibility, also called: making sense of the world without any conscious effort on my part. In sum, visualizing the deity Ziwei or Zhenwu in exquisite detail as infinite patterns and constant movement and then becoming him by replacing my passive sensory experience with a new passive sensory experience, is a demonstration of what it is to be a normal human being. The Golden Elixir is an act of making unconscious processes conscious, so that we can re-order the constituents of our being. It is an experience of reality—pockets of which are reducible to observable things, things that make sense and (re)constitute order. [See essay 2]

I mean think about it. We use the word trance in English, but what does it mean? It’s a catchall for 37 mind-body-mask-medicine practices in other cultures. Keith Johnstone called our culture trance-phobic.

The Golden Elixir is in this sense a land of extraordinary methods for making the ordinary extraordinary. But we return to what is normal (“Return is the direction of Dao”—Laozi); the most sacred of sacred Daoist fluids is plain water.

The methodist critiques of visualization, which are extremely common among martial artists, are correct at face value, 1) you can’t fight with an imaginary tiger doing the “work” for you, and 2) you will inhibit the self-arising refinement of emptiness if you are busy focusing on the image of a deity. But those critiques are missing the view. The view is that the inseparability of my actions and my perceptions is fertile ground for discovering the nature of reality. Maybe I can fight by becoming that imaginary tiger. The capacity to integrate visualization into movement is unequally distributed among the population. Those of us born with super-mega-power imaginations can’t help but use them all the time for everything. But one size does not fit all. The imagination can be a terrible tool for trying to teach the masses. The teacher has to know the student.

It’s the same thing with appetites, you can’t teach Tai Chi to plebs who have no innate desire to conquer the world. There is just nothing to leverage there.

This is all self evident if you have established zuowang as your base view. But it is hard to walk yourself into it by conceptual means (like reading a text). In fact, if you don’t have a sense of humor, it is a set up for frustration. And this, in a nutshell, is my critique of the methodists. Stand alone methods lead to frustration. Now you know why Zhuangzi just up and turned into a butterfly.

Yes, zuowang (Sitting & Forgetting) and jindan (the Golden Elixir) are secret esoteric transmissions. We don’t proselytize or advertise. But Daoist cosmology has been dominating Chinese art for two thousand years, and it has dominated Confucianism for the last thousand years, from Zhu Xi forward. This made mediation inherently accessible to earlier generations. The last Confucian dances were performed around 1910 and then went extinct. Communists, fascists and academics widely believed Daoism had gone extinct by the 1970s. (Kristopher Schipper gave a great talk about this). The centrality of Daoist cosmology before the 20th Century meant that someone teaching Daoist meditation wasn’t starting from scratch. It is an esoteric transmission, subjective if you will, but it was also common and normal. That kind of Golden Elixir came under attack and went into hiding. Now that China is dominated by NYC style skyscrapers, it is mostly forgotten. But as Methodists began dominating China in the early Twentieth Century, luminaries Chen Yingning & Zhao Bichen promoted and refined and tamed a methodist version of the Golden Elixir that grew out of monasticism and reason. It’s the most popular method now. Sad. We need something much wilder. [See Daoist Moderns, Liu Xun]

Another Golden Elixir teaching is the making of the immortal embryo.

I explained this in my book, but there are many different types. Starting over is literally in our DNA. Have sperm, will travel.

Here is a rule of thumb for looking at descriptions of the Golden Elixir, flip them upside down. Read them backwards, invert them. If they are authentic, it shouldn’t matter. The recipes are not progressive.

The immortal embryo is, obviously, a possible fruition of cultivating wuwei (not doing). The subject of the fourth essay in this series is Fruition.

I teach a monthly, two hour class in which I expand on commentaries of the Daodejing and leave students with a chapter to chant and digest as a way of transmitting Daoism. It requires a commitment to meditate for an hour everyday. Send me an email if you are interested.